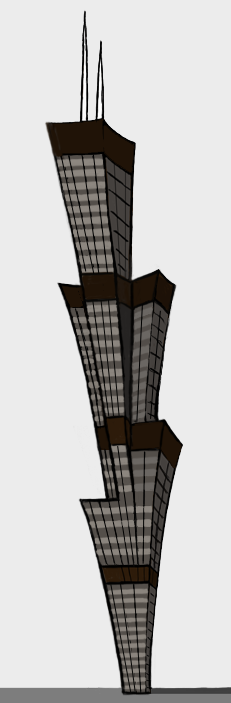

RICHARD S. DARGAN | Architecture

Willis Tower (formerly Sears Tower), Chicago | |||||||

|

Completed: 1973 Advances in materials and technology spurred dramatic innovations in Chicago building design in the decades after the Great Fire of 1871. The 12-story Home Insurance Building (1885) was the first building to utilize structural steel in its frame. The subsequent development of caissons—steel-reinforced concrete columns anchored into the bedrock 40 feet below the city—provided support for even taller, heavier structures, as explained in this video from Jim Janossy, Sr. These advances set the stage for the 1920s and the so-called First Wave of Chicago skyscraper construction, featuring landmarks like the Tribune Tower (1925), the Mather Tower (1928) and the Chicago Board of Trade (1930). The Second Wave arrived 30 years later thanks in large part to the work of Fazlur Khan, engineer and architect at Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM). Khan, a Pakistani immigrant, developed a new approach to skyscraper design in which the building's walls, or skin, bore much of the load. This “tubular” approach freed skyscrapers from the heavy metal skeletons of the past and enabled the construction of much taller buildings that were strong enough to resist lateral forces like wind. Tubular engineering also required fewer interior columns, opening up spaces inside. During the 60s, Khan experiment with several types of tubular buildings, starting with the framed tube Dewitt-Chestnut apartments (1963) and moving on to the trussed tube design of the 100-story John Hancock Center, completed in 1970. For the even taller Sears/Willis, Khan, working with SOM design chief Bruce Graham, designed a bundle of nine tubes, or modules, for greater strength and stability. The different heights of the modules create a series of setbacks that recall Deco era skyscrapers like the Empire State Building, with the stone cladding and narrow window strips of those older buildings replaced by bronze-tinted glass and black anodized aluminum spandrel panels set in frames of similar material. Depending on the weather and the angle of the sun, the building's surface colors can range from shimmering gold to jet black. The Sears/Willis Tower represented the apex of Chicago's Second Wave of skyscraper construction, and as with the earlier wave, a 30-year lull followed. The Third Wave is under way now, highlighted by the Trump International Hotel and Tower (2009), designed by—who else?—SOM and located next to the Wrigley Building on the river. At 110 stories and 1,450 feet, the Sears/Willis Tower held the title of tallest building in the world from 1973 to 1998, when it was eclipsed by the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur. Its massive east and west antennas—253 and 283 feet tall, respectively—are not counted in the building's official height because they are not considered architectural design features. Spires (e.g., the structure that tops the Empire State Building), on the other hand, are counted in a building's height.

|

||||||